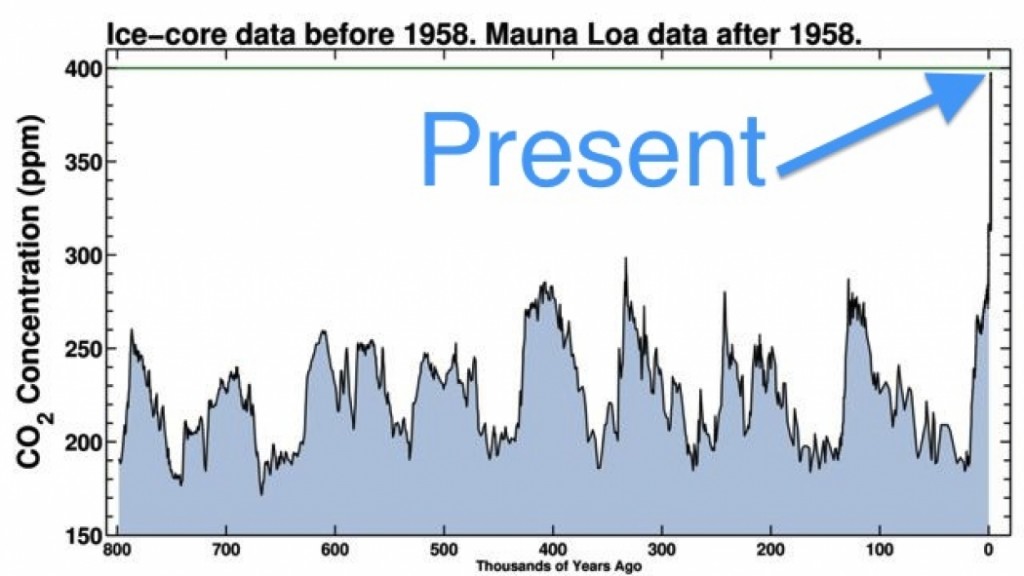

Der CO2-Gehalt der Erdathmosphäre ist mittlerweile auf einen Stand geklettert, der alle Werte der letzten 800.000 Jahre übertrifft (Abb. 1). Während der Eiszeiten sank die CO2-Konzentration bis auf 180 ppm ab, während er in den dazwischenliegenden Warmzeiten (Interglazialen) auf 250-300 ppm hinaufkletterte. Grund für diese CO2-Entwicklung ist vor allem das Ausgasen des CO2 aus dem wärmernen Interglazial-Wasser. Seit Beginn der Industriellen Revolution stieg der CO2-Wert jedoch auf Werte deutlich oberhalb der typischen Warmzeit-Spannweite. Aktuell besitzt die Atmosphäre einen CO2-Anteil von etwas mehr als 400 ppm.

Abbildung 1: CO2-Verlauf der letzten 800.000 Jahre. Quelle: Scripps Institution of Oceanography, via Climate Central.

Die große Frage ist nun, wie lange die Natur wohl brauchen würde, bis der antrhopogene CO2-Berg wieder abgebaut ist, sofern die CO2-Emissionen stark zurückgefahren werden könnten. Nehmen wir einmal an, von heute auf morgen würden Kohle, Öl und Gas verboten werden. In wievielen Jahren wäre der CO2-Überschuss vom natürlichen Kreislauf aufgenommen und aus der Atmosphäre verschwunden sein? Der 5. IPCC-Bericht schreibt hier, dass nach 1000 Jahren 85-60% des anthropogenen CO2 aus der Atmosphäre wieder verschwunden wären. Der vollständig Abbau würde aber mehrere hunderttausend Jahre dauern. In Kapitel 6 der Arbeitsgruppe 1 heißt es dazu:

The removal of human-emitted CO2 from the atmosphere by natural processes will take a few hundred thousand years (high confidence). Depending on the RCP scenario considered, about 15 to 40% of emitted CO2 will remain in the atmosphere longer than 1,000 years. This very long time required by sinks to remove anthropogenic CO2 makes climate change caused by elevated CO2 irreversible on human time scale.

Laut Umweltbundesamt (UBA) geht es aber auch schneller. Auf der UBA-Webseite wird angegeben:

Kohlendioxid ist ein geruch- und farbloses Gas, dessen durchschnittliche Verweildauer in der Atmosphäre 120 Jahre beträgt.

Von einem ähnlichen Wert geht auch Mojib Latif aus: Infranken.de berichtete am 13. Januar 2016 über einen Latif-Vortrag im Rahmen einer Lions-Club-Veranstaltung:

“100 Jahre bleibt CO2 in der Luft”

Der Klimaforscher Professor Mojib Latif machte als Gastredner beim Neujahresempfang des Lions-Clubs auf den Klimawandel aufmerksam. […] “Wenn wir CO2 in die Luft blasen, dann bleibt das da 100 Jahre”, so Latif.

Hermann Harde von der Helmut-Schmidt-University Hamburg beschreibt in einer Arbeit, die im Mai 2017 im Fachblatt Global and Planetary Change erscheint und bereits vorab online verfügbar ist, einen neuen Ansatz, der Hinweise auf eine viel kürzere CO2-Verweildauer in der Atmosphäre liefert. Laut Harde bleibt das überschüssige CO2 im Durchschnitt lediglich 4 Jahre in der Luft:

Scrutinizing the carbon cycle and CO2 residence time in the atmosphere

Climate scientists presume that the carbon cycle has come out of balance due to the increasing anthropogenic emissions from fossil fuel combustion and land use change. This is made responsible for the rapidly increasing atmospheric CO2 concentrations over recent years, and it is estimated that the removal of the additional emissions from the atmosphere will take a few hundred thousand years. Since this goes along with an increasing greenhouse effect and a further global warming, a better understanding of the carbon cycle is of great importance for all future climate change predictions. We have critically scrutinized this cycle and present an alternative concept, for which the uptake of CO2 by natural sinks scales proportional with the CO2 concentration. In addition, we consider temperature dependent natural emission and absorption rates, by which the paleoclimatic CO2 variations and the actual CO2 growth rate can well be explained. The anthropogenic contribution to the actual CO2 concentration is found to be 4.3%, its fraction to the CO2 increase over the Industrial Era is 15% and the average residence time 4 years.

Dieser Wert ist nicht zu verwechseln mit der Verweildauer von einzelnen CO2-Molekülen in der Atmosphäre. Hier herrscht weitgehend Einigkeit, dass die Moleküle selber nur einige Jahre in der Luft bleiben, bevor sie mit CO2 aus dem Meerwasser im Sinne einer Gleichgewichtsreaktion ausgetauscht werden.