Im März 2013 betitelte Joachim Müller-Jung einen Artikel in der FAZ sehr treffend mit

Wer die Welt simuliert, hat die Wahrheit nicht gepachtet

Wie viel Realität steckt in Klimamodellen? Fakt ist: Die Komplexitäten nehmen zu, die Unsicherheiten aber auch. Wie kann die Forschung da glaubwürdig bleiben?Weiterlesen auf faz.net.

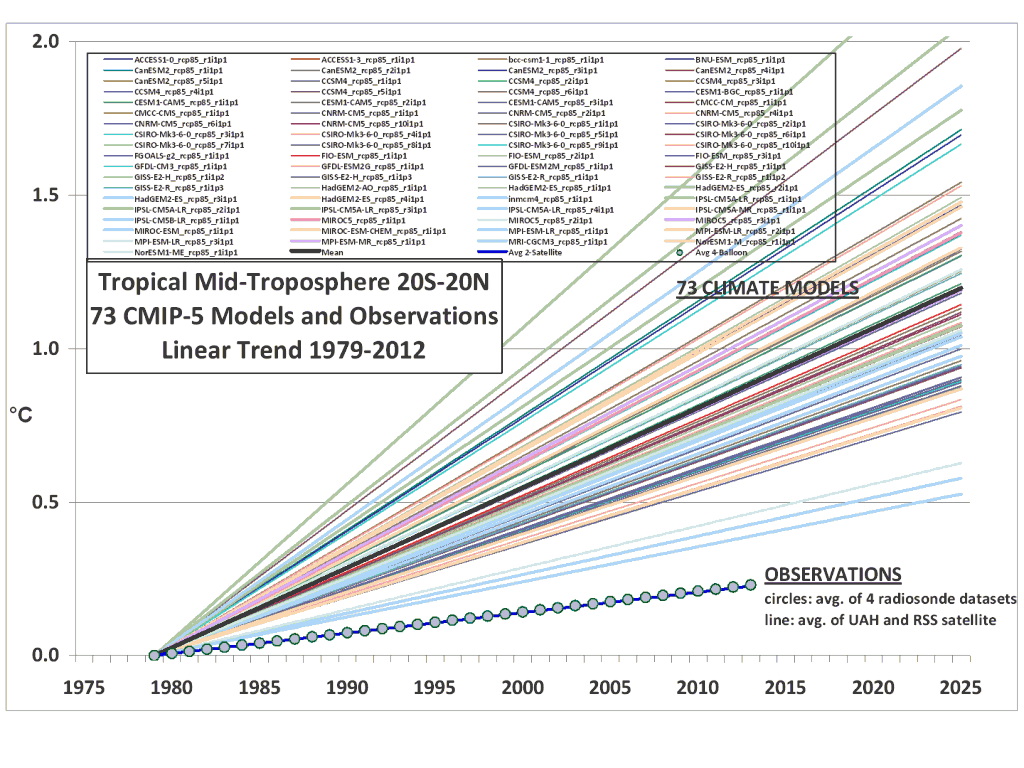

Wir wollen heute einen weiteren Streifzug durch die Modellierungswelt wagen. Die Branche befindet sich bekanntlich in einer tiefen Sinnkrise. Man hatte eifrig drauflos modelliert aber die zahlreichen Prognosefehlschläge gehen mittlerweile an die Substanz. Eine erste Welle der Selbstkritik geht durch die Fachwelt. Nicht alles ist so rosig wie man es lange nach außen hin und gegenüber den staatlichen Geldgebern dargestellt hatte.

Am 21. Februar 2013 gab die Universität Göteborg eine Pressemitteilung heraus, dessen Titel bereits aufhorchen lässt: „Die Klimamodelle sind nicht gut genug“. Im Rahmen eines Promotionsprojektes wurde herausgefunden, dass Klimamodelle die in den letzten 50 Jahren in China beobachteten Veränderungen der extremen Regenfälle nicht nachvollziehen können:

Climate models are not good enough

Only a few climate models were able to reproduce the observed changes in extreme precipitation in China over the last 50 years. This is the finding of a doctoral thesis from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Climate models are the only means to predict future changes in climate and weather. “It is therefore extremely important that we investigate global climate models’ own performances in simulating extremes with respect to observations, in order to improve our opportunities to predict future weather changes,” says Tinghai Ou from the University of Gothenburg’s Department of Earth Sciences. Tinghai has analysed the model simulated extreme precipitation in China over the last 50 years. “The results show that climate models give a poor reflection of the actual changes in extreme precipitation events that took place in China between 1961 and 2000,” he says. “Only half of the 21 analysed climate models analysed were able to reproduce the changes in some regions of China. Few models can well reproduce the nationwide change.”

Probleme mit der Regenmodellierung gibt es aller Orten. Auch in den USA kriegen die Modelle die historische Niederschlagsentwicklung einfach nicht in den Griff, wie Mishra et al. (2012) und Knappenberger und Michaels (2013) zeigen konnten. Ähnliches fanden Stratton & Stirling (2012) und Ramirez-Villegas et al. (2013) auf globaler Ebene. Auszug aus der Kurzfassung des zuletzt genannten Papers:

Climatological means of seasonal mean temperatures depict mean errors between 1 and 18 ° C (2–130% with respect to mean), whereas seasonal precipitation and wet-day frequency depict larger errors, often offsetting observed means and variability beyond 100%. Simulated interannual climate variability in GCMs warrants particular attention, given that no single GCM matches observations in more than 30% of the areas for monthly precipitation and wet-day frequency, 50% for diurnal range and 70% for mean temperatures. We report improvements in mean climate skill of 5–15% for climatological mean temperatures, 3–5% for diurnal range and 1–2% in precipitation. At these improvement rates, we estimate that at least 5–30 years of CMIP work is required to improve regional temperature simulations and at least 30–50 years for precipitation simulations, for these to be directly input into impact models. We conclude with some recommendations for the use of CMIP5 in agricultural impact studies.

Soncini & Bocchiola (2011) hatten sich den Schneefall in den Italienischen Alpen angeschaut. Auch hier wieder das gleiche Bild: Die real gemessene Entwicklung kann von den Modellen nicht reproduziert werden. Schlimmer noch, die Zukunftsprojektionen verschiedener Modelle weichen stark voneinander ab. Hier die Kurzfassung der bemerkenswerten Arbeit:

General Circulation Models GCMs are widely adopted tools to achieve future climate projections. However, one needs to assess their accuracy, which is only possible by comparison of GCMs’ control runs against past observed data. Here, we investigate the accuracy of two GCMs models delivering snowfall that are included within the IPCC panel’s inventory (HadCM3, CCSM3), by comparison against a comprehensive ground data base (ca. 400 daily snow gauging stations) located in the Italian Alps, during 1990–2009. The GCMs simulations are objectively compared to snowfall volume by regionally evaluated statistical indicators. The CCSM3 model provides slightly better results than the HadCM3, possibly in view of its finer computational grid, but yet the performance of both models is rather poor. We evaluate the bias between models and observations, and we use it as a bulk correction for the GCMs‘ snowfall simulations for the purpose of future snowfall projection. We carry out stationarity analysis via linear regression and Mann Kendall tests upon the observed and simulated snowfall volumes for the control run period, providing contrasting results. We then use the bias adjusted GCMs output for future snowfall projections from the IPCC-A2 scenario. The two analyzed models provide contrasting results about projected snowfall during the 21st century (until 2099). Our approach provides a first order assessment of the expected accuracy of GCM models in depicting past and future snowfall upon the (Italian) Alps. Overall, given the poor depiction of snowfall by the GCMs here tested, we suggest that care should be taken when using their outputs for predictive purposes.

Bloß aus den Wolken gegriffen?

weiter lesenNoch mehr Spaß mit Klimamodellen: Es will partout nicht passen