Die Gletscher des Mt. Baker im US-Bundesstaat Washington schrumpfen derzeit. Das haben sie aber auch schon 1915-1950 getan. Davor und danach sind die Gletscher gewachsen. Die aktuelle Schmelzphase begann dann um 1980 und dauert noch an. Das lustige Gletscher-Jojo hat der US-Gletscherforscher Don Easterbrook eindrucksvoll auf WUWT beschrieben. Besonders interesant: Um 1950 waren die Gletscher sogar noch kürzer als heute:

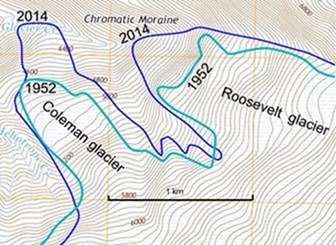

Abb. 1: Positionen der Coleman and Roosevelt Gletscherfronten in 2014 (blau) und 1952 (grün). Quelle: Easterbrook 2015, WUWT.

Die University of Fairbanks fand heraus, dass auch ganz andere Faktoren als die Temperatur eine Rolle spielen, speziell bei im Meer mündenden Gletschern. Dort können Gletscherrückzüge auch durch sich verschiebende Sedimente verursacht werden. Andere Forscher der Alaska-Gletscher zeigen sich klimahistorisch eher kurzsichtig, da sie ihre Vergleiche in der Kleinen Eiszeit beginnen, anstatt bis zur letzten natürlichen Warmphase vor 1000 Jahren zurückzugehen. Interessant ist zudem dass die Gletscher Alaskas offenbar mehr als die Hälfte ihrer Masse bereits vor 1950 verloren hatten, als der menschliche Einfluss auf das Klima noch sehr gering war. Ähnlich sieht es wohl im Yosemite-Park aus, wie Thomas Richard beschrieb.

Stansell et al. 2015 beschrieben oszillierende Gletscher in den peruanischen Anden:

Late Glacial and Holocene glacier fluctuations at Nevado Huaguruncho in the Eastern Cordillera of the Peruvian Andes

Discerning the timing and pattern of late Quaternary glacier variability in the tropical Andes is important for our understanding of global climate change. Terrestrial cosmogenic nuclide (TCN) ages (48) on moraines and radiocarbon-dated clastic sediment records from a moraine-dammed lake at Nevado Huaguruncho, Peru, document the waxing and waning of alpine glaciers in the Eastern Cordillera during the past ∼15 k.y. The integrated moraine and lake records indicate that ice advanced at 14.1 ± 0.4 ka, during the first half of the Antarctic Cold Reversal, and began retreating by 13.7 ± 0.4 ka. Ice retreated and paraglacial sedimentation declined until ca. 12 ka, when proxy indicators of glacigenic sediment increased sharply, heralding an ice advance that culminated in multiple moraine positions from 11.6 ± 0.2 ka to 10.3 ± 0.2 ka. Proxy indicators of glacigenic sediment input suggest oscillating ice extents from ca. 10 to 4 ka, and somewhat more extensive ice cover from 4 to 2 ka, followed by ice retreat. The lack of TCN ages from these intervals suggests that glaciers were less extensive than during the late Holocene. A final Holocene advance occurred during the Little Ice Age (LIA, ca. 0.4 to 0.2 ka) under colder and wetter conditions as documented in regional proxy archives. The pattern of glacier variability at Huaguruncho during the Late Glacial and Holocene is similar to the pattern of tropical Atlantic sea-surface temperatures, and provides evidence that prior to the LIA, ice extent in the eastern tropical Andes was decoupled from temperatures in the high-latitude North Atlantic.